Review by Geoff Dyer

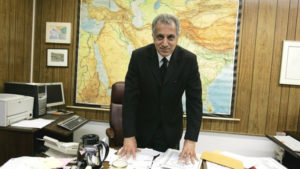

©Getty Zalmay Khalilzad in Kabul in February 2005, towards the end of his term as US ambassador to Afghanistan. He would go only to serve as ambassador to Iraq and ambassador to the United Nations.

From Dick Cheney to Donald Rumsfeld, the administration of George W Bush has come to be defined by its most abrasive personalities. But one of the most intriguing individuals to play a leading role in the Bush-era wars is Zalmay Khalilzad, a polished diplomat who was the most senior Muslim in the White House at the time of the 9/11 attacks, and who has now published his own memoir, The Envoy.

Born in northern Afghanistan, the son of a local official, Khalilzad rose to be US ambassador in both his home country and in Iraq following the occupation, a time when the role was more viceroy than envoy. A card-carrying neoconservative, he also had an understanding of the Middle East that was lacking in his overconfident colleagues.

Were it not for the fact that Khalilzad was deeply involved in one of the greatest blunders in the country’s history — the invasion of Iraq — his memoir would read as a genuinely triumphant American success story.

Khalilzad’s upbringing was comfortable by the standards of Mazar-i-Sharif, the third-biggest city in Afghanistan — but those standards were not high. Of the 13 children his mother gave birth to, only seven survived. He still remembers the night his sister Hafiza passed away, after crying desperately for days. He believes she had appendicitis.

In the spring, his home town radiated with wild red poppies, while storytellers spun tales to crowds about battles from the early days of Islam. His favourite pastime was competitive kite-flying. “Before launching your kite, you carefully soaked the string in a mixture of mushy boiled rice and pulverised glass, turning it into a flying razor,” he writes. “Then you took aim against the strings of your adversaries.”

A year as an exchange student in California turned his head, however, and after studying at the American University of Beirut he did a doctorate at the University of Chicago. He intended to return to Kabul and enter politics; instead, he stayed in the US and worked as an Afghanistan expert, helping to organise American support for the rebels fighting the Soviet occupation.

Yet it was only with 9/11 that “Zal” became an indispensable member of the administration. “I was the highest-ranking Afghan-American and Muslim-American at the White House,” he writes, although it took a while for the significance of his background to sink in. Wolfowitz later admitted: “We were a week into this crisis before it hit me that Zal was from Afghanistan.”In his instincts, Khalilzad showed himself to be close to the neoconservative thinkers who were starting to exert a strong influence over the Republican party. He was an early supporter of a policy of regime change in Iraq and, alongside Cheney, Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz, he was a founding member of the Project for the New American Century, a neocon think-tank that called during the Clinton years for “American global leadership”. When George W Bush won the presidency, he was rewarded with a senior White House job.

After the fall of Kabul, a White House meeting debated what to do with Burhanuddin Rabbani, a former president who had fought with the mujahideen. Khalilzad surprised his colleagues by saying: “I can call Rabbani if you want.” He became a close adviser to Bush on Afghanistan, revelling in the manoeuvring that surrounded the choice of Hamid Karzai as president. In 2003, he returned to Kabul as the US ambassador.

Although he had long called for the toppling of Saddam Hussein, Khalilzad was also an early critic of how the invasion was conducted, telling Bush that the initial plan to quickly devolve power had been replaced by “an occupying force like the one that had ruled defeated Japan after World War II”. Dissolving the Iraqi army was a massive “own-goal”.

If he had wanted more headlines, Khalilzad could have taken his book in two directions. He could have written a mea culpa about why Iraq went so wrong. Instead, he only writes that he left Iraq in 2007 after two years as ambassador “profoundly disappointed”. Alternatively, he could have tried to argue that the invasion might have worked, if done his way. Such a counterfactual argument would persuade few people but if anyone could pull it off, it might be Khalilzad.

Instead, he conducts a subtle inside job on the Bush administration. Khalilzad details not only the failure to plan for the day after the invasion but also the lack of intellectual preparedness at the White House. He credits Bush for insisting the US was not at war with Islam — something that in this year’s Republican primaries would be an act of political bravery. But he also recalls a meeting with Bush shortly after 9/11 when he described the anguish of Muslims about the decline of their civilisation from a time when it led the world in education and science. “‘It was a civilisation on the march,’ I said.”

“Now, come on, Zal!” the president interrupted teasingly. Andrew Card, the White House chief of staff, intervened: “I think Zal is referring to the Ottoman Empire.” Khalilzad writes: “I gently noted that . . . the apex of Islamic civilization . . . had come earlier, under Arab leadership.”

Source: Financial Times